Active, closed-loop flow control is a category of flow control methods that involves energy input (active) and a method of changing the actuation based on measurements of the system (closed-loop). This style of flow control is appealing because it can offer greater control authority over passive and open-loop methods. Modern experimental tools provide methods for observing the state of the system and for rapidly reacting to changes in the state (e.g., Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems). However, a major challenge lies in determining the optimal actuation policy. As such, we work on developing computational methods for discovering active flow-control strategies.

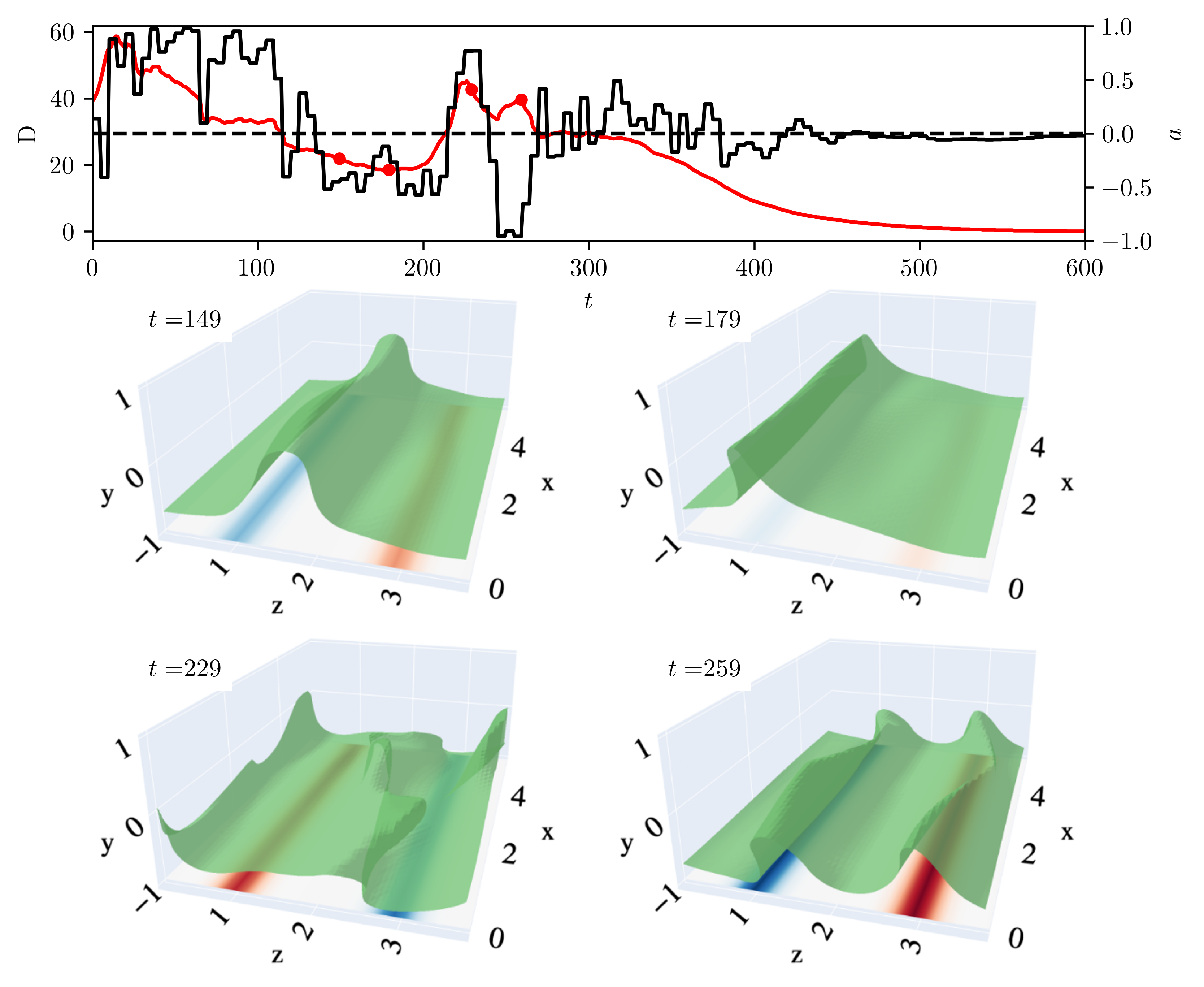

Example of turbulent flow control. The top panel shows drag (red) and the wall normal velocity of the left jet (black). The right jet actuations in the opposite direction. The lower panels show snapshots of the flow with isosurfaces of the streamwise velocity. This highlights the location of low-speed streaks. Here, the RL agent finds a method to laminarize the flow by generating two low-speed streaks. This temporarily increases drag, but disrupts the natural streak spacing, which leads to laminarization.

Two methods for finding control algorithms are reinforcement learning (RL) and model predictive control (MPC). We use methods like these to discover close-loop control algorithms in high-resolution simulations -- the results of which could be applied to physical systems. Those in controls often refer to these simulations as surrogate models. In RL, a neural network agent repeatedly interacts with this surrogate model to find a policy that maximizes a reward. In MPC, a set of actions are chosen, then the surrogate model is evolved forward and an adjoint model is evolved backwards to compute the gradient of a reward with respect to this set of actions. This gradient is then used to select a new set of actions.

Applying these types of approaches for tasks such as drag reduction remains a major challenge due to the high computational cost of forecasting, the ambiguity in selecting flow actuators, and the high sensitivity of fluid systems. Thus, a major thrust of our research involves developing fast algorithms for discovering active flow-control strategies. For example, we have found that we can couple low-dimensional models with RL and MPC to minimize drag in turbulent channels using fluid jets (Linot et al., 2023).

References

2023

-

Turbulence control in plane Couette flow using low-dimensional neural ODE-based models and deep reinforcement learning

Alec J. Linot, Kevin Zeng, and Michael D. Graham

International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, Jun 2023

The high dimensionality and complex dynamics of turbulent flows remain an obstacle to the discovery and implementation of control strategies. Deep reinforcement learning (RL) is a promising avenue for overcoming these obstacles, but requires a training phase in which the RL agent iteratively interacts with the flow environment to learn a control policy, which can be prohibitively expensive when the environment involves slow experiments or large-scale simulations. We overcome this challenge using a framework we call “DManD-RL” (data-driven manifold dynamics-RL), which generates a data-driven low-dimensional model of our system that we use for RL training. With this approach, we seek to minimize drag in a direct numerical simulation (DNS) of a turbulent minimal flow unit of plane Couette flow at Re=400 using two slot jets on one wall. We obtain, from DNS data with O(105) degrees of freedom, a 25-dimensional DManD model of the dynamics by combining an autoencoder and neural ordinary differential equation. Using this model as the environment, we train an RL control agent, yielding a 440-fold speedup over training on the DNS, with equivalent control performance. The agent learns a policy that laminarizes 84% of unseen DNS test trajectories within 900 time units, significantly outperforming classical opposition control (58%), despite the actuation authority being much more restricted. The agent often achieves laminarization through a counterintuitive strategy that drives the formation of two low-speed streaks, with a spanwise wavelength that is too small to be self-sustaining. The agent demonstrates the same performance when we limit observations to wall shear rate.